Leah Pistorius

April 15, 2024

Robots are increasingly becoming a part of our daily lives at home, at work, and even in public spaces. But how do people want to interact with robots? This is a question that has been on the mind of Dr. Elin Björling, an affiliate faculty member and senior research scientist in the Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering, for nearly a decade.

Dr. Björling has a background in psychology and in the development of new technologies aimed to improve mental health. At UW, she co-directs the Momentary Experience Lab, where she collaborates on open-source projects that both capture data and intervene to improve health. In Autumn 2023, Björling brought her research questions to HCDE students through a new master’s course on designing human-robot interactions.

Through her research projects using robotics to combat stress in teenagers, Björling has gathered a lot of social robots. “Often robots hit the market and there’s a lot of buzz, and then the enthusiasm around them dies down and they get put on a shelf until the next thing comes out,” Björling said. “I have a hunch that’s because most of these robots don’t have strong use cases – they’re not solving real problems or meeting real human needs. So, I wanted students in this class to really get creative and uncover new needs that may be appropriate for social robots.”

Finding a human need

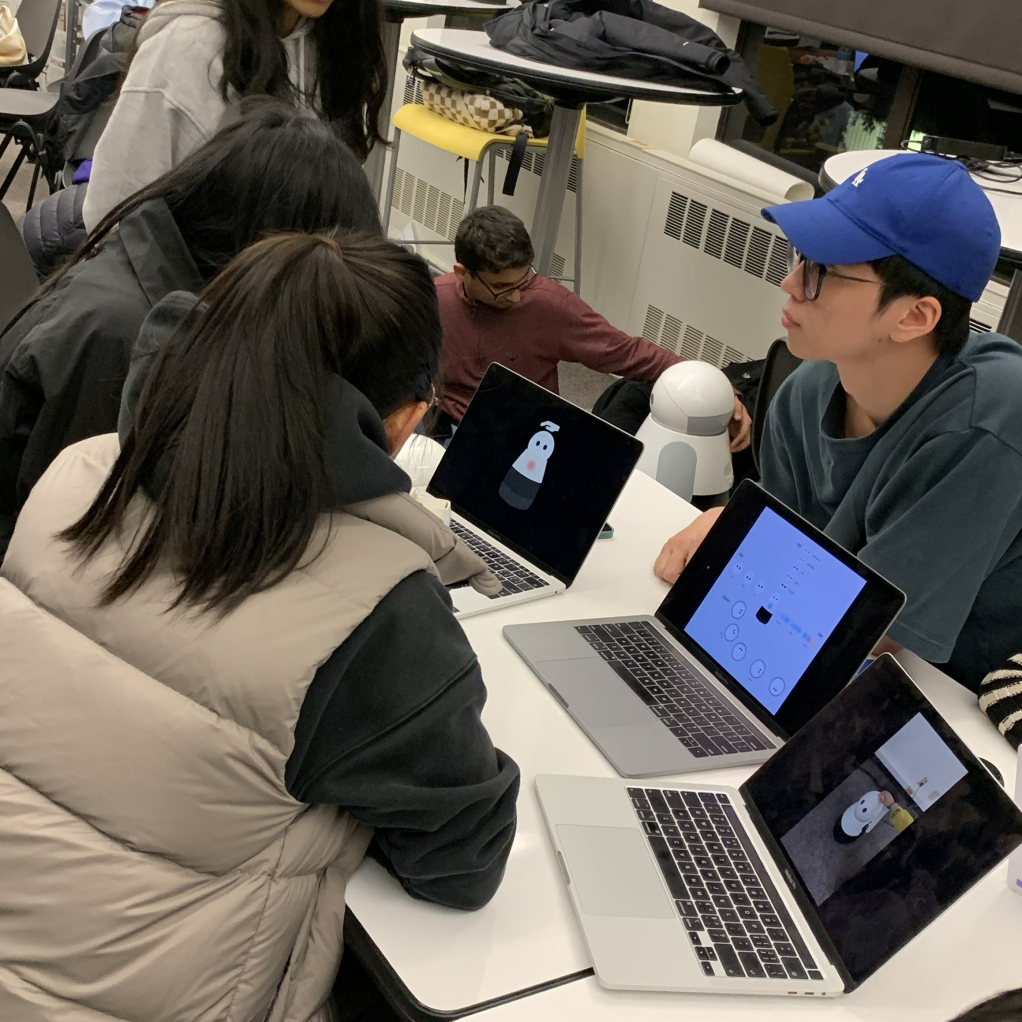

Through a mix of readings, guest lectures, and hands-on projects, students in the class explored a diverse range of social robots and topic areas. For the final project, Björling assigned teams of students a specific robot and a domain area to design for, like customer service, mental health, or companionship.

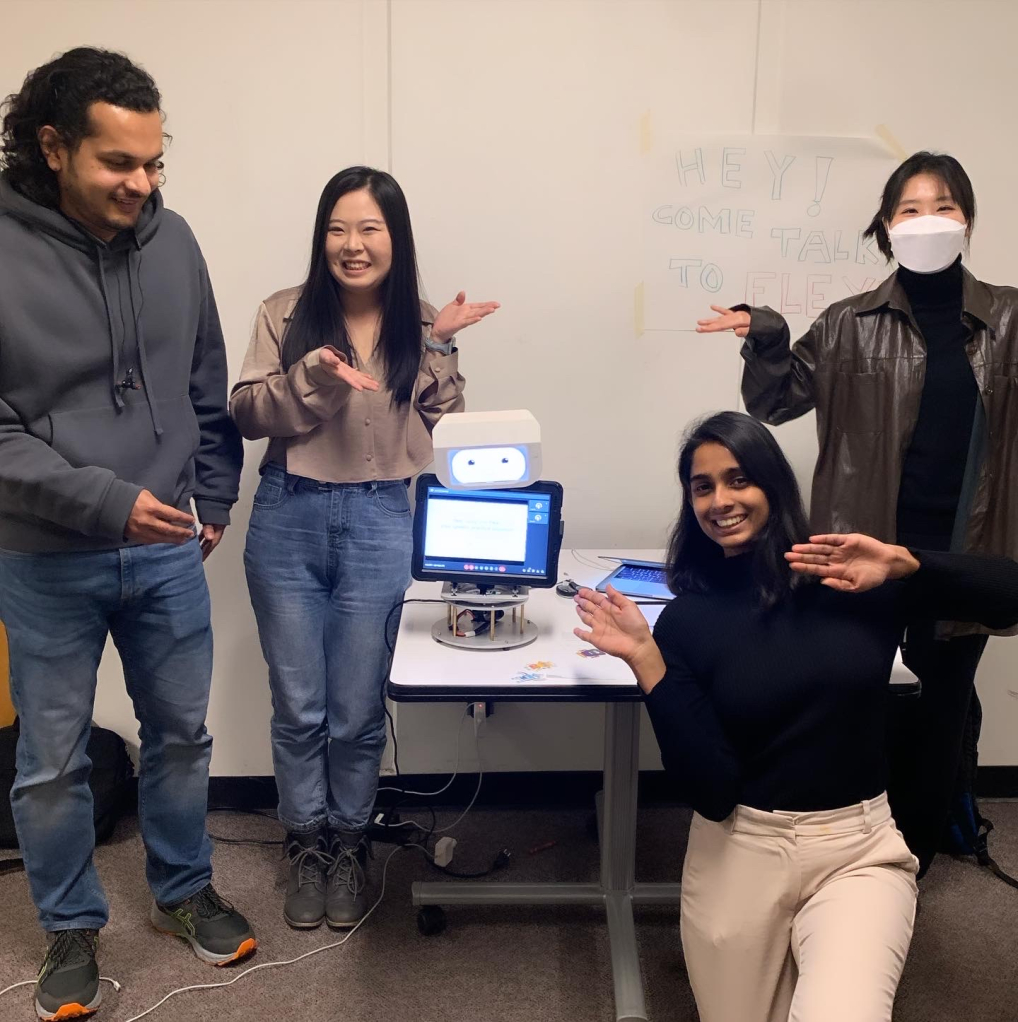

Students in HCDE's Human-Robot Interaction course designed new scenarios for social robots and constructed robot prototypes to test the interactions.

Flynn Robinson, a first-year master's student in HCDE, was on a team assigned the domain of companionship with NAO, a robot with arms and legs that can walk, dance, speak, and recognize faces.

“NAO is small and playful so we wondered if young people might be receptive to interacting with it,” said Robinson. “The two other people on my team were mothers, so we had great in-house expertise with kids, and we started talking about a very real issue for some young people, which is encouraging children to take breaks when playing video games.”

Crys Sahae, a second-year master’s student in HCDE, was on a team assigned FLEXI, a fully customizable robot kit developed by Björling and her collaborators in the Momentary Experience Lab.

“We were assigned security as a domain, and to be honest, I was not excited about security at all,” Sahae said “I love so many aspects of what social robots could be and their potential, but security felt like we were going to be spending all quarter designing a robocop.”

Trying to steer the project away from something that could be used for harm, Sahae and her teammates asked themselves how they would want to see robotics used for security out in the world. “We recalled this idea of a ‘digital shield’ that Elin had told us about, which is using technology as a proxy between two humans,” she said. “So we started exploring how a robot could work in conjunction with law enforcement while acting as a buffer – like an empathetic and supportive presence that could support vulnerable people.”

Designing human-centered interactions

Robinson’s team researched child-robot interactions, the impacts of gaming on youth well-being, and interviewed parents and kids about their experiences with gaming. “We found patterns in our research, including that kids will prioritize playing games over their immediate well-being, and that they are receptive to robot instruction for their own health benefit,” said Robinson.

Robinson’s team brainstormed possible scenarios in which NAO could encourage a child to take a break, while still incorporating a playful experience. Robinson learned the programming language for NAO and built a prototype to test with potential users.

Their NAO robot is a companion that delivers timely interruptions during video game play and incentivizes the child to do a physical activity like dance, answer a riddle, or drink water. Through play, the robot educates the child about the benefits of exercise and health, and modifies its responses based on the child's previous preferences, feedback, and choices.

Master's student Flynn Robinson and their team developed a NAO robot companion that intervenes during video game play to encourage children to take breaks and engage in physical activities. Their NAO companion integrates playful experiences and personalization to educate children about exercise and health.

Delving into the concept of a digital shield, Sahae and her teammates explored possible contexts for a robot within the security domain. “Our research led us to survivors of sexual assault, and how they can be re-traumatized when reporting their experiences to law enforcement,” she said. “So our primary goal was to design an empathetic experience that can gather the necessary data from survivors in a supportive and non-judgmental way.”

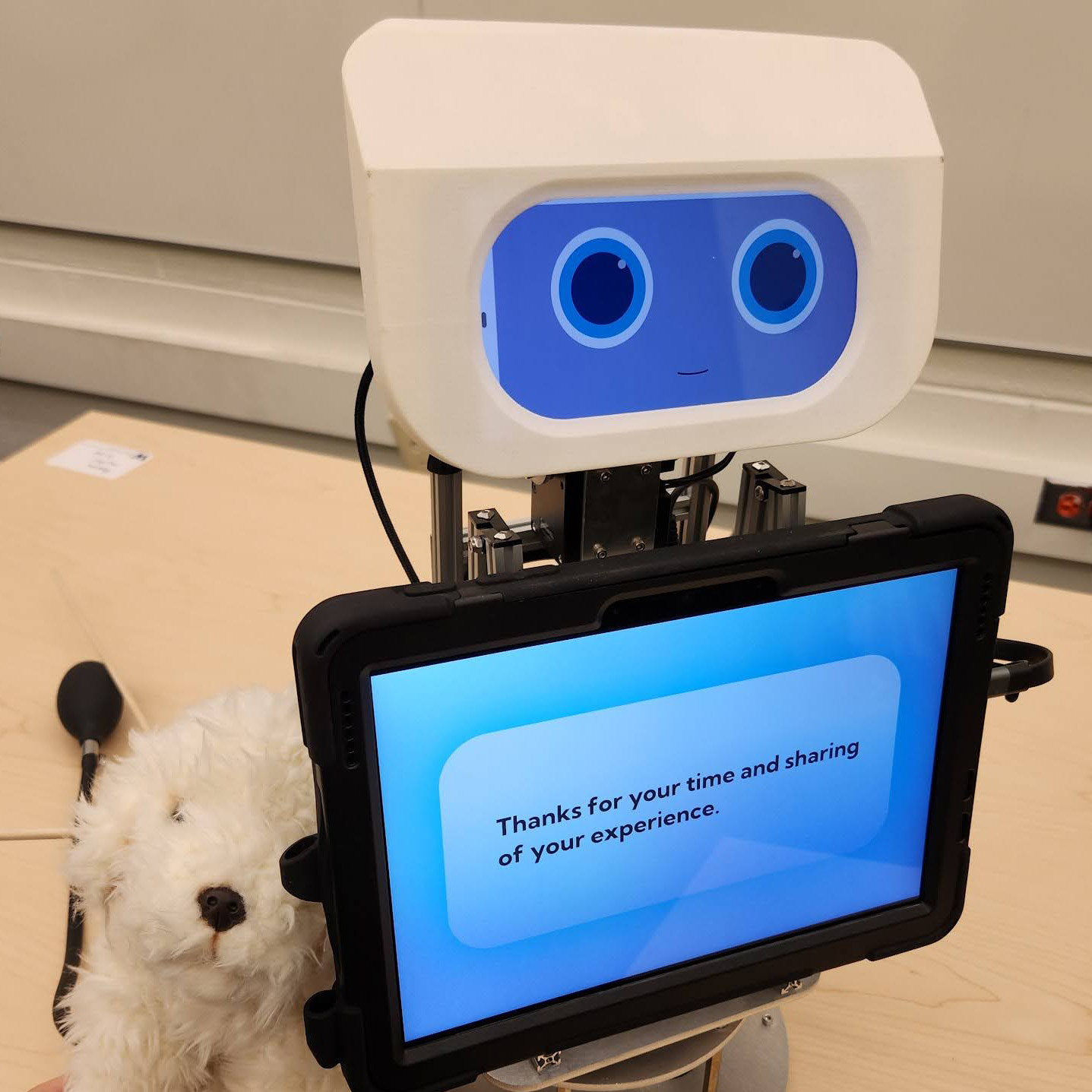

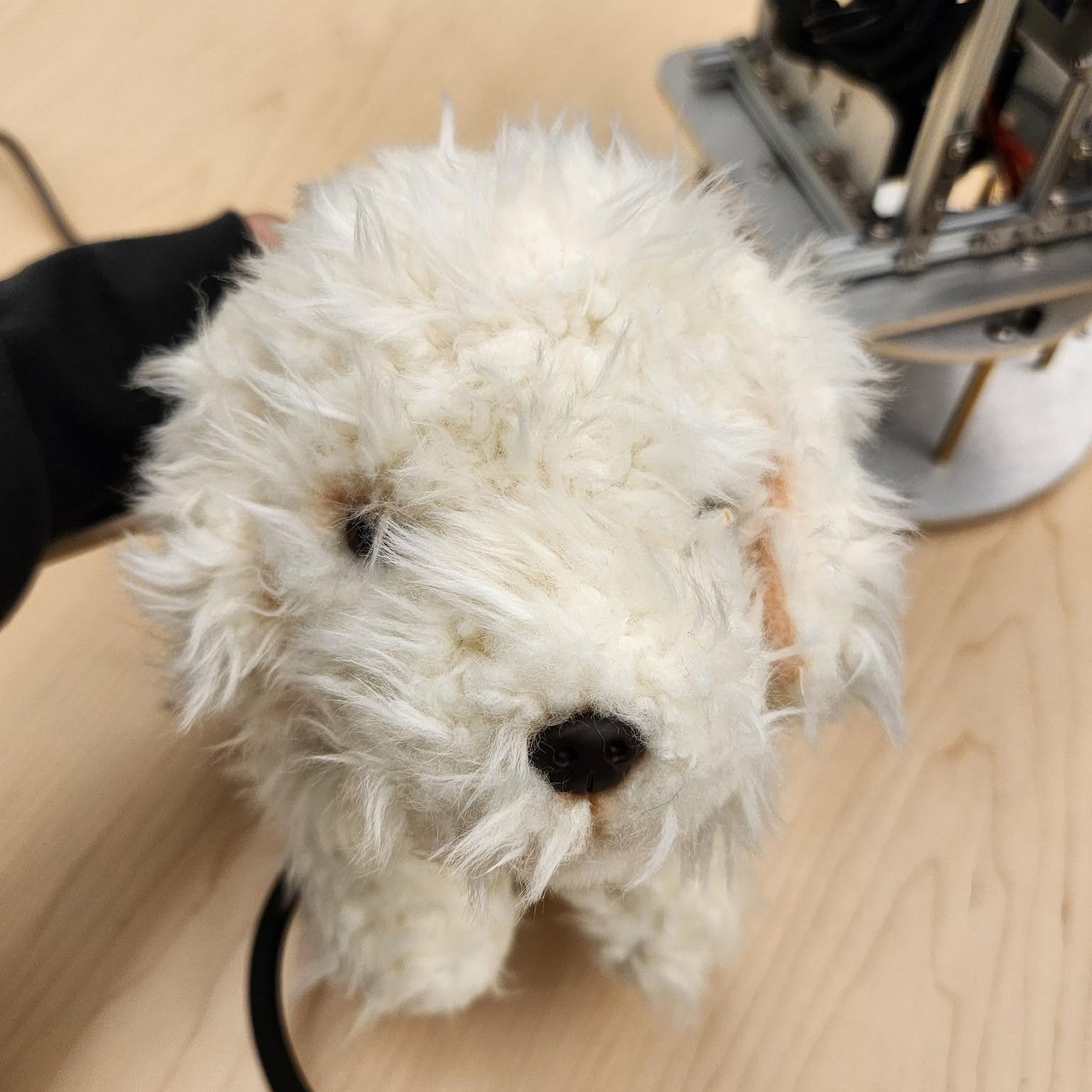

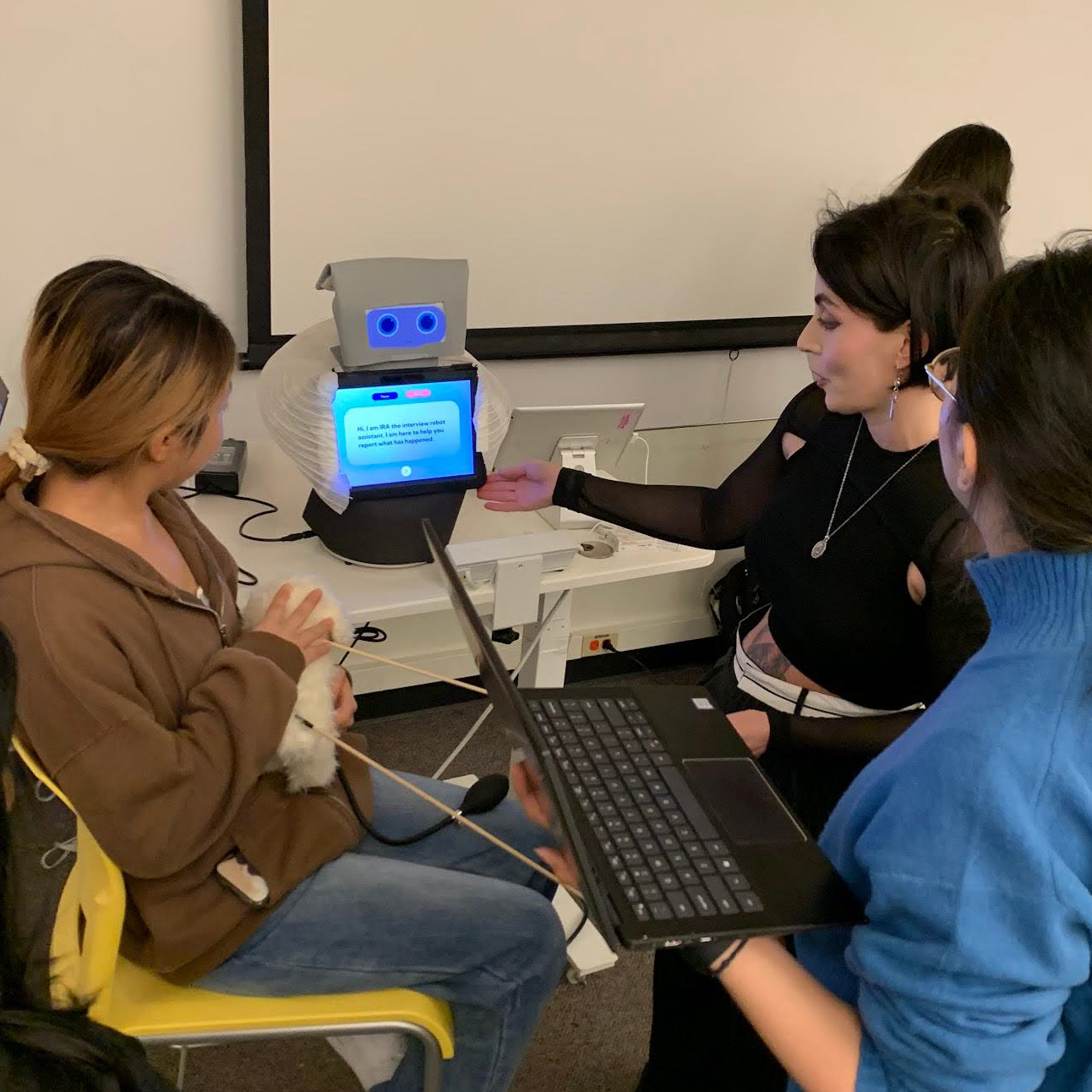

Sahae’s team developed a prototype for IRA (the Interview Robot Assistant) that supports survivors in reporting their experiences from the safety of a trusted person's office or hospital room. They also incorporated findings on emotional support animals and developed a companion robot, Pup, that offers emotional support and records physiological data. Using AI, IRA takes the police questions and analyzes them for supportive and appropriate language. Together with Pup, IRA delivers the questions in a supportive manner and offers the survivors a break when they are stressed.

Master's student Crys Sahae and her team designed IRA (the Interview Robot Assistant) and companion robot Pup to provide empathetic support for survivors of sexual assault during reporting, gathering necessary data in a non-judgmental manner while incorporating emotional support and breaks when needed.

Björling invited the HCDE community and her colleagues from industry to a mid-quarter showcase where the students tested their prototypes and got feedback before finalizing their designs.

"I think all of these projects are beautiful, creative applications of social robots that are meeting real human needs,” said Björling. “Nobody's been coming up to me like, you know we need a robot at a police station to help victims report, or we need a robot to help kids with healthy screen time. These have not been known needs for robotics. But as the students started talking to people about real challenges, they’ve uncovered these places where robots could play a really unique and useful role,” she said.

A future with social robots

Project videos

Learn more about two student projects, NAO and IRA, in the videos below.

Interview Robot Assistant (IRA): Working Toward Robot Assisted Sexual Assault Disclosure

Team: Crys Sahae, Nichelle Song, Shay Gu, Lige Yang

Gamified Breaks: NAO Companion for Healthy Screen Time

Team: Flynn Robinson, Candelaria Herrera, Hamedia Jemal

Both Robinson and Sahae said this course inspired them to continue exploring robotics in the future.

“As a first-year student enrolling in this class, I had no idea what I really wanted to do. And I'm coming out chanting ‘Robots!’,” said Robinson. “Robotics as a field can feel really intimidating, but one thing I loved about this class was that Elin – who is not a robotics engineer by trade – kept emphasizing that the field needs more of us who bring that human-centered lens. We obviously need roboticists, but we also need social scientists, designers, and all forms of researchers. There’s so much opportunity here, and it’s really exciting.”

Sahae believes that ubiquitous, well-designed robots in the future will do what other technologies have done for people in the past. “I think we’re going to see certain menial tasks offloaded onto robots and open greater potential for the human mind,” she said. “If we can get to a future where people can offload more menial tasks it will let them hyper-specialize in the things they love, helping people get to a better work-life balance.”

“We can fashion robots to be whatever we want them to be. And we have to understand that something that works in one space is not going to be appropriate for another,” said Robinson. “It’s important to ask where robots should be and where they shouldn’t be, and the best way to find this out is by working really closely with people to understand their unique needs.”

Björling hopes that this course reinforced “universal truths” about good technology design. “Robotics or not, I want the students to understand that when designing any technology, we need to first start with meeting a human need,” she said. “Who will be interacting with this thing? What do they need it to do and how do they want it to do it? These are questions all technology designers need to be asking in order to create real solutions to real problems.”